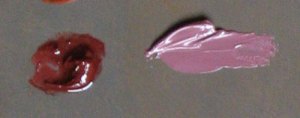

Here is a somewhat better pic of the cool colors of the paint swatches (from left: ultramarine, turquoise, amazonite, malachite) from the last post:

Still having trouble photographing that amazonite – it’s really quite saturated out of the tube, but you’d never know it from looking at this.

The paints themselves: overall they were fine to use. Upon first opening, some of them (especially the malachite) gave off a distinctly rancid oil aroma, even though they were bought directly from Daniel Smith. Not a big deal, of course, though the smell of linseed oil is normally one of the (many) pleasures of working with oil paint.

The paints are very smooth, which personally I don’t particularly like; part of the joy of working with natural pigments is the sometimes grainier texture, which seems completely absent from these paints. I personally would like to feel the “naturalness” of these natural pigments under the brush; of course, other painters might disagree (in fact, I know at least one personally who does disagree). For me, missing out on that is missing part of the point of using natural pigments in the first place.

The vehicle for these paints is alkali-refined linseed oil (alkali-refined means it’s chemically processed), with the exception of the two blues (Turquoise and Lapis), which use alkali-refined safflower oil instead. Again, the choice of binders seems to me to miss the point of the paints: if you’re making a big deal out of using natural pigments, wouldn’t you want to use a natural oil to go along with them? (It’s not nearly as bad as wasting natural pigments in a thoroughly synthetic medium like acrylic, of course, but still.) Maybe it’s just me, as an enthusiast of natural art materials: but having these paints in a natural, raw, cold-pressed linseed oil, along with some greater variation in pigment particle size, would make these paints much more exciting.

Lightfastness: For some reason, the only one of these paints that has lightfastness information listed on the Daniel Smith website is the Malachite Genuine, which is listed as having “Lightfastness Rating: I.” Others of these pigments are available in watercolors and do have lightfastness ratings listed: Rhodonite Genuine, Purpurite Genuine, Lapis Lazuli Genuine, Sleeping Beauty Turquoise Genuine, Amazonite Genuine, and Malachite Genuine are all listed as “ASTM Lightfastness Rating: Excellent” in watercolor. However, there have been some lightfastness problems noted by various artists who have done their own tests. Note the changes in the Rhodonite, for instance, here by annie.nz on WetCanvas. Again note the Rhodonite here on Jane Blundell’s blog, and also the Sleeping Beauty Turquoise. These two posts seem to indicate there may be some question about those lightfastness ratings provided by Daniel Smith. (At the same time, I’ll note a general consensus that many pigments have greater lightfastness in oil than in watercolor, possibly mostly because of the thicker paint layers used).

Here are two test paintings done with the Daniel Smith Primatek paints. This first one is a sketch of some of the blue irises blooming in the backyard (the same irises from which I get the green ink). The background was done with some paints from Da Vinci and Rublev; the flower and plant parts were done with the Primateks, with some help from Rublev’s Blue Ridge Yellow Ochre and Lemon Ochre.

I was expecting to be able to use the Purpurite for the flowers, but that color loses too much saturation in tints. As I mentioned earlier, I was able to get better violet tints with a mix of the Rhodonite and the Lapis. (I still had to steer the tints more toward the magenta, since the Rhodonite is so much stronger than the Lapis.) The Purpurite was fine for the darker violets. Amazonite, Malachite and a bit of Turquoise did a fine job for the green plant parts, and in fact were more saturated than I needed – except for the brighter chartreuse bits, which were helped along with some of that lemon ochre.

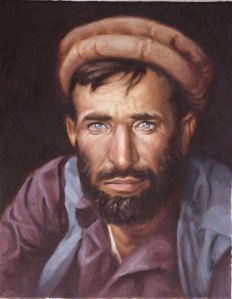

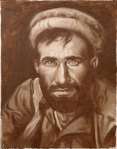

Here is another test, a portrait of my wife Joy. For this one I used the Primatek Sedona, Pipestone, Rhodonite and Turquoise; Rublev supplied the yellow ochre, black and white.

I went a bit mad with color on this one; it’s actually quite scandalous for me, who usually uses just earth colors (and maybe a touch of madder) for skin tones. A bit of a color theory experiment, really, that was only partially sucessful. Early in the painting I got the urge to use some of the Turquoise for the flesh tones, and it worked very well for that. The Rhodonite worked fine as well, mixing nice oranges with the yellow ochre, and rose tints with white. You can see how rich the color is in the shirt; if it were just a touch redder in hue I’d probably use this paint regularly.

Overall these Primatek oil paints will be a welcome, if occasional, addition to my palette; and I have to give a lot of credit to Daniel Smith for choosing some of these unusual pigments. I’ve been wanting to try painting with natural turquoise for a long time, and it was a pleasure to finally do so, especially in the portrait. Along with that paint, the clear winners here are the Amazonite Genuine and the Rhodonite Genuine – both stunning paints that can actually compete with some of the modern synthetic organics. The Purpurite is also fun for those dark violets, and the Sedona Genuine is a good-quality, if fairly ordinary, natural red ochre. Even the three disappointments in my set – the Minnesota Pipestone, the Genuine Lapis Lazuli, and the Malachite Genuine – are still useful paints (although the Pipestone may be relegated to underpaintings, since it’s such a weak tinter). At the end of the day, I can recommend Daniel Smith’s Primatek line of oil paints for those interested in painting with natural pigments. Give them a try; and feel free to post the results back here!

Thanks for reading!